When Blurred Lines Help

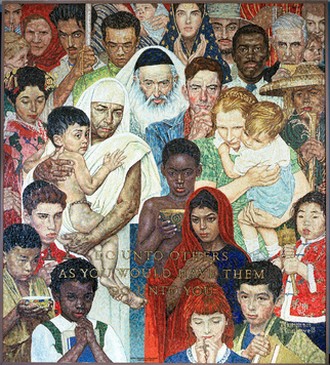

I was lucky enough to spend a day at an interfaith event that took place as part of World Interfaith Harmony Week. It’s focus was sharing ideas about the different religions present. Jainism, Baha’i, Judaism, Natural Pantheism, Paganism, Christianity, Islam the list went on.

Two things struck me that day.

One was how those religions, and others present, complimented each other. How when points of similarity are emphasised, points of difference blur.

One God Many Voices

Rabbi David Mivasair ended his talk that day with a story from Hebrew oral tradition. In the Midrash Rabbah, the story goes, God spoke at Sinai in seven voices and each voice went forth in seventy languages.

It’s a simple and poetic picture for the diverse ways we hear, and so understand, God.

It reminds me of the story of the elephant behind the screen. The one where an elephant is hidden behind a curtain with slots large enough only for a hand to go through. Different people slide their hand though the hole and when asked to describe the thing behind the screen, they can’t agree. One says “It’s hard and pointed at the end,” another, “It’s very wide and thin, rough to the touch.” And another still, “It’s long and thin and hairy at the end.” A tusk, an ear and a tail. All parts of the same creature. Each on their own, difficult to see as being part of the same animal.

Like Rabbi David’s story, it sums up the need for things like World Interfaith Harmony Week.

Moving The Conversation On

Interfaith events like the one I attended aren’t rare and they don’t just happen on World Interfaith Harmony Week. If you’re in the States, Harvard’s Pluralism Project holds frequent events with the mission of “helping Americans engage with the realities of religious diversity through research, outreach, and the active dissemination of resources”. If you’re in Canada. The Interfaith Observer plays a similar role and if you’re in the UK have a look at The World Congress of Faiths.

It’s refreshing to see while that “mind-numbingly circular” debate for or against God I mentioned in my last post drones on (and on, and…), there’s still a real desire for some to share ideas about God.

Letting Go

I said there were two things that struck me at that event. The other was this. At the end, when everyone was tidying up or stacking chairs, a man handed me a booklet. It told me Jesus was my saviour.

That simple, no doubt well intentioned, gesture speaks volumes about how difficult it is for some to let go of their one fixed idea about God.

Hold On, Lose Out

It’s holding on to one fixed idea about God that could be the reason younger generations are giving up on God. Although a survey released earlier this month by the Public Religion Research Institute points the reason squarely at a perceived anti-gay bias in organized religion, Jon Terbush writing in The Week offers a broader view. The “outright hostility to science from some on the right,” Terbush writes, “— on global warming, evolution, and even something as seemingly benign as vaccines — only further impugns religion’s credibility with younger voters. It should be no surprise then that solid majorities of Millennials describe Christianity as “hypocritical” and “judgmental.”

Is it any surprise belief in God is losing ground? Put simply, if God really were as some right wing religious views depict it, then God too would be hypocritical and judgemental. Who wants any part of that?

Interfaith: The Beginning of A New View

World Interfaith Harmony Week isn’t about glossing over the problems of religion. It’s about respect for all religions.

And here’s something else it could be: the beginnings of a new way of looking at God. One that sees God not just present in all religions, but transcending religion as well.

Imagine that for a moment.

In a world that sees its religions as an attempt to understand God rather than having the definitive take on God everything changes. It means we can put religious differences aside, knowing one view is no more complete than another. It means we can start working together to solve some of the world’s problems. It might even mean we attempt to solve those problems with a sense of equality, justice and integrity.

And then who knows what kind of world we’d create for oursleves.

© Joe Britto and God 4.0, 2014. All rights reserved.